I once stood in the courtyard of an apartment house in Mombasa, Kenya, watching residents try to chase off mosquitoes using the fumes from burning cow dung. Children near to the fumes were crying but, in a country where mosquito-born diseases such as Malaria and Dengue Fever kill tens of thousands per year, the discomfort seems worth it.

I had visited the site to install a wind generator system to supply back-up power to a base transceiver station. The scene was a catalyst that started me thinking about ways to introduce insecticide vaporisers to rural communities in Kenya. I met a like-minded graduate at the Cambridge University and, having attended the Smart Villages Graduate Forum, we hatched a plan.

In Kenya, increasing numbers of people spend their evenings socialising and studying with artificial lights as the national power grid expands and the electrification rate rises. In contrast to the many species of mosquito that bite people at night, some malaria vectors bite earlier in the evening. Although LLTINs (Long-Lasting Insecticide Nets) have been commonly used to reduce the risk of mosquito-transmitted infections during sleep, additional protection is needed for the periods of dawn and dusk, when the encounters between active people and active mosquitoes is most common.

The Government of Kenya has implemented Kenya National Malaria Strategy 2009-2017 (NMS) with several international organisations such as President Malaria Initiative (PMI). The strategy has five focus areas: insecticide treated net, indoor residual spraying, malaria in pregnancy, care management, and surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, and operational research.

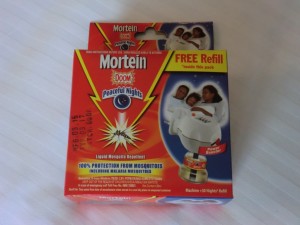

We originally had assumed that there would have been few vaporiser products available in Kenya, and this was not the case. During the on-site research in Kenya in early July, we found many insecticide vaporisers in supermarkets. Three types are identified: liquid, mat/chip, and coil. The average price of liquid and mat/ship types was 400 – 750 Kenyan Shilling (KES) and that of coil was around 30 KES. The price at hundreds of KES is affordable for residents in urban areas but too expensive for rural villagers and low-income families in townships. Furthermore, users of vaporisers need to refill the insecticide every 1 to 2 months, incurring the regular cost of buying alternative liquid bottles and mats/chips. The LLITNs were sold in shopping centres at the cost of 500 – 2300 KES, which is very expensive for rural villagers. However, each net can last approximately five years. Many LLITNs have been distributed for free of charge by the government and international organisations, and LLITNs are now the primary measure for mosquito control.

Two team members visited communities in Mbita and Rusinga Island in Western Kenya, where it was found that most residents used LLITNs in their house, and that few other products were used for mosquito control. Interestingly, large numbers of workers on Rusinga Island do not spend their evenings or nights indoors because they work as fishermen, typically between 7pm and 3am. Furthermore, one villager on the island said: ‘distributing more than two LLITNs might not reduce the malaria infection because typical houses do not have enough space for hanging more than two LLITNs.’

A researcher of International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) similarly argued: ‘Children aged between 5 – 15 years old are exposed to highest risk of malaria infection because they sleep in living rooms or kitchens without LLITNs. Parents and little children below the age of 5 usually sleep in LLITNs.’

Observations made during on-site research lead us to suggest that insecticide vaporisers would bring tangible benefits as an additional measure of malaria preventive intervention. However, we identified at least four main challenges: cost burden in product and electricity, mosquito’s increasing resistance to insecticides, changes to the national insecticide registration system, and a shortage of education in mosquito control. Going forward, we will seek to develop affordable and reliable solutions by communicating with the government, vaporiser manufacturers, NGOs, and community members.