… in the context of the Service Value Test (SVT), a key tool in the Smart Villages approach which engages community members to uncover their needs and aspirations for the future development of their village. It’s an important early step when we start working with a new community, and the quantitative and qualitative data about what services the community prioritises is fed into the design process for an energy system. Find out more about it here. Initially developed during Anna’s PhD to assist in the design of two mini-grids in Kenya, it has been deployed in multiple SVRG projects spanning Tanzania, Uganda, Somaliland, and Lesotho. In the first stage, participants suggest services which they want to see in their community in the future. What is becoming very clear, though, is the challenges that occur when ‘electricity’ is suggested as one of the services that participants want to be able to access.

Don’t get us wrong, it is a really reasonable suggestion and happens pretty much all the time in our experience. All villages we have come across already have extensive experience with some forms of electricity generation and systems, such as batteries, solar home systems, solar lanterns, and diesel gensets. Everyone is aware of grid electricity and people have really good ideas about how it could make their lives easier. To understand why it’s difficult to cope with ‘electricity’ as a suggested service in an SVT, we have to go a little into the approach that we take in design and what we do with the SVT data.

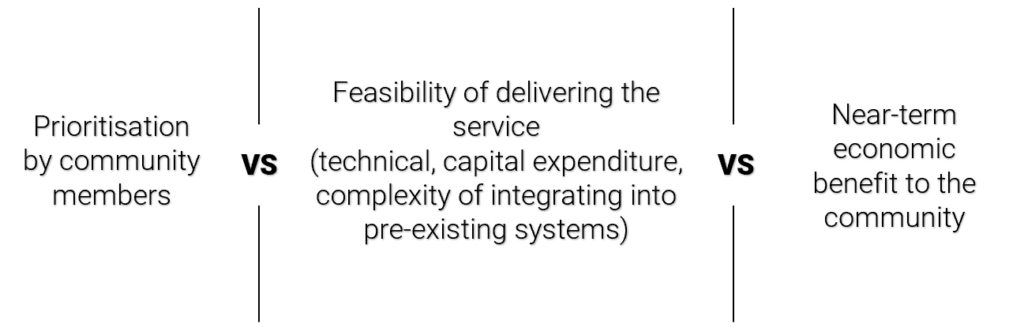

Once participants have suggested services, they use counters to indicate their preferences (see photo). After the focus group, we process the data so that we can use it to guide our decision making in choosing which services the energy system should provide. How do we make decisions about which services to choose? Although ideally we’d love to be able to design a system to meet all community needs, or at least, definitely the ones which are highest priority, there are of course technical, logistical, and financial constraints to energy system design. There may also be a priority area of development for the community, or associated with the particular project – for example, perhaps a key outcome required is that community members are able to save time, benefit from income-generating opportunities, or that women in particular benefit. As in most design situations, we end up wrestling with trade-offs in various decision criteria. For example:

Without a structured analysis approach, this messy multi-criteria situation might lead to suboptimal design decision-making. In particular, what we don’t want to do is let our own biases or preferences tip us towards ignoring the data and picking services that we like the sound of, but which aren’t based on feasibility, community benefit, and community preferences. That’s why there is a structured process to analyse the SVT results against the various design decision criteria, and map the results on what we call service maps.

This service map positions the services on axes which are the decision criteria. The community preference data is there too, in the size of the bubble, and the colour represents how many focus groups suggested that service across a community. By mapping the services like this, we can clearly see the trade-offs between the various decision criteria. Services might be hugely popular with the community, but very challenging to implement (e.g. household electric cookers), or have high economic benefit, but not be a key community priority (e.g. welding services). It helps us see what decision criteria we are meeting by picking certain services, and be cognisant on what isn’t being optimised. The map doesn’t solve our design challenge, but it’s a really useful tool and crucially, makes sure the community preference data is brought right alongside the engineering considerations, and other project aims, when we’re making design decisions.

So, what if someone suggests ‘electricity’? Our problem with electricity as a service in an SVT is that it’s too vague. How are we ever going to assess it’s technical ease of delivery, or its potential near-term economic benefit to a community, if we don’t know any more than the word ‘electricity’?. It’s not possible, and so makes it impossible for us to include electricity on the service maps. In many of the countries in which we work, the words for electricity and lighting can be used interchangeably, which makes defining and assessing the suggested service even more challenging. The solution is easy – we just ask: ‘So what would you use that electricity for?’ and we’re back on track. Now we know why electricity is of interest, and what community members are thinking to do with it – essentially, the end use or service that electricity would provide access to – we can include it in our design decision-making. In smart villages, we take a service-oriented approach. It’s not about the electrons, it’s about what one can do with those electrons that matters more to both the end users, and to us for our design work.

We discuss the SVT in more detail in another post.

For more on the detail of SVT method and analysis, click the image below.