Interview with Josephine Marie Godwyll

Founder and National Coordinator at Young at Heart Ghana

Location: Ghana

“The missing link most of the time is information”.

Rural communities have a tremendous amount to gain from access to information. The internet offers potential solutions to many of the problems that make rural life difficult, but these are only valuable if local people can access them. Luckily, training rural children in computer skills doesn’t have to be expensive. That’s the message of Young at Heart Ghana, which brings university students—and their laptop computers—to the countryside as volunteer educators.

Back in 2011, a 27-year-old geomatic engineer named Josephine Marie Godwyll traveled to a rural Ghanaian village to volunteer in a school there. Although she is Ghanaian herself, the experience opened her eyes. Students weren’t being taught basic computer skills, largely because rural schools didn’t own the necessary equipment.

“We were raising a generation of half-baked graduates, who had only theoretical experience of science, engineering, and math,” Godwyll said. She felt like the future of the country was literally at stake. In a nation where health and public records are still often kept on paper, she believes the future would be brighter if the next generation of workers was literate in digital skills.

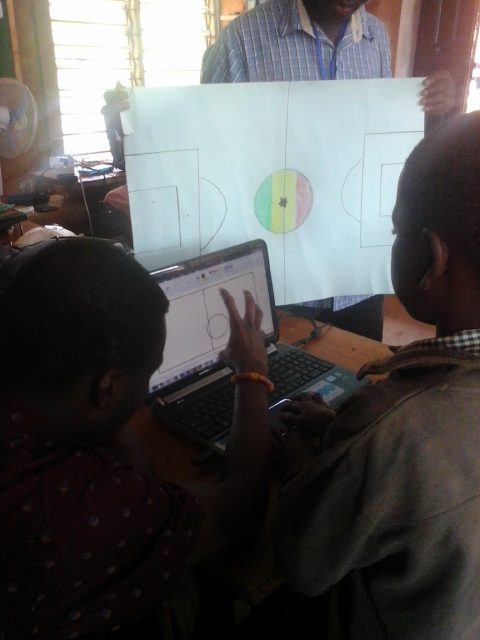

The challenge was to get working computers into the villages where rural children lived. The expense of purchasing them was prohibitive. So in 2012 Godwyll came up with a solution so cheap and simple it almost seemed too good to be true. She went to the association of students in computer science at Kwame Nkrumah University and asked whether the members would be willing to bring their personal laptops to the countryside to train kids who lived there. A handful said yes, and Young at Heart Ghana was off the ground.

Since then, the nonprofit organization has become larger and more sophisticated. Young at Heart raised more than US$17,000 in its third year, more than six times what it raised in its first. The group has a formal training programme for its teachers and operates in four different regions of Ghana. It has developed its own software that illustrated lessons about computers using “Anansi the Spider,” a well-loved character in local folklore. It has established permanent computer labs using donated equipment, where teachers can go beyond teaching basic literacy.

While Young at Hearth used to work only with kids 15 years old and younger, it now teaches more advanced classes to older children as well. Some of these programmes focus on skills like graphic design and promotion, which students use to strengthen their families’ businesses. The group also makes money on robotics classes it teaches in urban areas. Yet the core of the project is still university students bringing their own laptops to villages.

An important challenge, according to Godwyll, is that potential partners and donors tend to leap to the conclusion that the project must be expensive. “They forget that we’re using volunteers who have laptops available,” she said. Over time, she’s emphasized measuring costs and impacts, which help to address those concerns. For example, she learned that one week of training at Young at Heart’s hub in the town of Akaa increased students’ technology test scores by 30 percent. She says it’s easier to get support when she explains the impacts and the role of volunteers together.

Another challenge was the gendered difference in student behavior. “Typically you have guys really excited,” she said. “The girls are a bit more chill. They think it’s outside their zone”.

The most effective solution Godwyll has found is to have some classes be just for girls. That way, the young women won’t be intimidated by the young men. What’s more, it allows the teachers to use examples that make sense to the girls, whose experience often centers around the home and the family shop. “It’s really affected by what they can relate to and what they’re most comfortable with,” Godwyll said. “Breaking it down based on gender helps you get closer to what they will understand”.

In five to 10 years, Godwyll hopes to expand the project to other African countries, where university students can again be rallied to solve similar problems. By participating in programmes such as the Mandela Washington Fellowship, she believes she’s already building the network that will support that expansion.

Godwyll hopes that her work will allow more people to remain in their rural homes. “I think that mostly people tend to want to leave rural areas because they believe that urban areas offer more opportunities—like better education and better access to health care.” But the expansion of the internet offers local people new opportunities to make progress in these areas, as well as ways to make their farms more profitable. “The missing link most of the time is information,” Godwyll says.

That’s why she focuses on the improvement of digital literacy among the continent’s youngest people. “If we can empower children to access information through mobile phones and computers,” she said, “then they can serve as the link between the people and the information they lack.”

—James Trimarco, Writer and researcher