[:en]

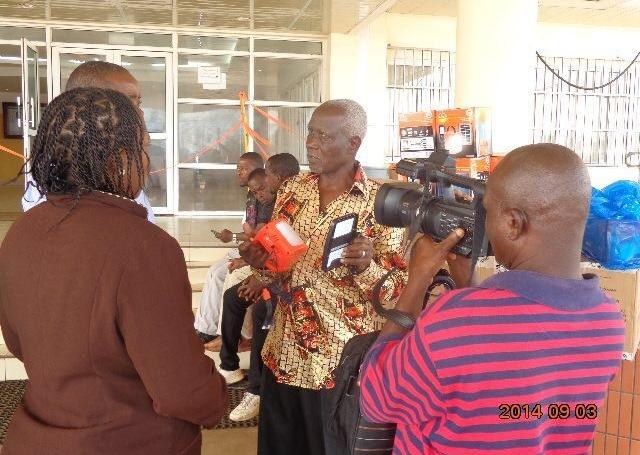

Richard Fahey, CEO, Liberian Energy Network (LEN)

Location: Liberia

“We give Liberians, be they fishermen or child soldiers, a powerful tool to do their job better”

When a shipment of solar lights disappeared at the port of Hamburg en route from China, only to turn up three months later, every single battery dead. It was the early days of the Liberian Energy Network (LEN). Founder Richard Fahey had spent his whole budget on the pilot, hot on the heels of a focus group with locals. After 14 years of civil war, less than 2% of the rural population are connected to the grid – that’s half of the population of 4.5 million. Only 10% in urban areas can access the grid.

The process of getting a technician out from Denmark, as suggested by the lights company, would take too long. “I thought we were dead in the water,” he says. Abubakar K. Sherif, president of the company, led Fahey out onto the streets of Monrovia. The plan was to find a mechanic, someone with their head under a bonnet, who might know how to to work with LED battery acid. The LEN office at the time was a “dark, hot, humid basement with one lightbulb” downtown where David, a former child soldiers, examined the batteries; “We need to go and see George”, was the prognosis. The investigation led them to George in what seemed like a cavern, the floor littered with batteries and pools of acid. George knew how to rebuild batteries. “He had one of the few connections to the tiny little grid that existed in Monrovia,” remembers Fahey. “We sat in that dank basement for a week and a half! Everything is about managing failure!”

For Fahey, the “huge” lesson when it comes to development and enterprise, is that Liberia – “despite being a tough place to do business” – has the resources to solve problems with what they have. “We didn’t have to fly in an electrical engineer from Europe. Locals are just otherwise sitting there, forced to do nothing,” says Fahey. The Liberian Energy Network employs a team of 12 locally. There is always a technician on staff, to service the lights people are getting, as well as two new engineer recruits. As a social enterprise, it provides services and goods at the base of the pyramid. “Rather than driving around and giving out lights off the back of a lorry to a bunch of needy people and thinking that’s development, the overarching approach is how to do high volume, low margin business.”

LEN sells most of its products goods; for Fahey, the ideal situation would be to absolutely break even, where cost would equal revenue. “It’s been an interesting journey,” he says. “The idea is not to reinvent the wheel. Mostly in development people take the ‘lunar module’ approach – doing something, leaving and not changing anything aside from leaving a few footprints. There are a lot of layers to it; we also want to create social capital.” Being a fellow at Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative, where he formulated LEN, “cut several years off the learning curve,” says Fahey, who describes the year-long experience as valuable, and was also where he recruited his co-founder. “The most important thing is that we had the opportunity to really vet the idea with really smart people who could tell me I was nuts, or were encouraging. It can be a dangerous thing to talk to yourself a lot – and convince yourself you’re ahead of the curve.”

Fahey directs back to the key idea behind LEN – to create a market and deliver goods. This is why fishermen are as much on LEN’s visor as former child soldiers (via a USAID Youth Advancing Project) or a 24-hour theatre at a hospital in Bong County. “I give them a new powerful tool to do their job better that adds value to their lives and their efforts. We’re looking at the market for electricity and power.” LEN has also worked with Save the Children to provide solar lights for kits 150 clinics.

Mostly, says Fahey, the approach in development is transactional. “Reputation is important, and we branded ourselves, which is fairly unusual there. Trust in our brand is a powerful tool for future engagement and development. We have also created a database.” When Fahey volunteered for the peace corps in Liberia in the sixties, he remembers making one phone call by payphone. The mobile phone market had no competition. “Frankly, I stole the idea when I was there in 2009 and looked around!” he laughs, about the desire to make Liberia the first country to be powered by the sun. “Why spend of tens of thousands of dollars build great big grids and stationary transmissions, when you just do what’s happened with phones!”

14,000 lights have been distributed so far, including 6,000 lights to children and teachers in Gbopolu County. 300 lights were given out during the Ebola crisis, which killed 5,000 in Liberia. During the latter, LEN helped improved site security around the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research (LIBR). There are challenges ahead. The goals is to “distribute more than 100,000 solar lighting units at a value of over $5,300,000 USD which, with an average of over 5 people per household in Liberia, will provide safe, reliable lighting for nearly 15% of the country’s population”.

The next, key step is to scale. LEN needs to access financial resources; the “extremely weak” banking system in Liberia doesn’t help. “I could show any other commercial bank that we have a viable market, model and goods which meet the needs of the market, and come up with some lines of credit. That doesn’t exist.” Thus far, it’s been hard, says Fahey. LEN has got by on self-funding and enjoyed the aid of a couple of individual angel investors. In 2016, a 100,000 USD grant from the US Africa Development Fund led to a project at the Firestone rubber plantation. 10,000 workers, many belonging to the Firestone Agricultural & Workers Union (Fawul), live and work here, and now access solar lighting via microlending.

Inspiration also came from more high-level quarters, in the form of a fortuitous two-hour meeting with president Ellen Sirleaf. Fahey was an attorney visiting the country, since he had experience of land law in Liberia. He spoke to Sirleaf about the barriers of a country which has struggled with a two-decade long civil war. “I wanted to know, despite the president’s great plans, how you get over the barrier of trauma and disorganisation, where people don’t feel empowered to make progress? She, being very smart, turned the question on me. She called my bluff. The president told me I was viewed as part of the diaspora, and told me to do something about it!” So Fahey did.

Nabeelah Shabbir @lahnabee

[:]