The Service Value Test (SVT for short) is a key tool in the Smart Villages approach that we like to use as early as possible in our conversations with communities we are looking to work with. We find it really helpful for the following reasons:

- It gets us quantitative preference data from community members telling us what they prioritise for the future development of their village. What services do they envisage as being part of their future development, and what would they prioritise?

- It tells us the backstory to those quantitative preferences – why are certain services important and why not others?

- It gives us a glimpse of the village context, in terms of:

- their current ways of doing things (their practices), the advantages of those ways but also the drawbacks

- their thoughts and aspirations (sometimes called cognitive norms) – how they think about their situation and what’s important to them about it.

- the infrastructure, products and services that already exist in the village or around (their material culture)

- It’s a relationship building activity, so we get to know them and they get to know us.

- It demonstrates to the community that we want to be led by their needs and aspirations, and so starts to show them that we will be working together on any project that emerges, rather than it being led by the wazungu.

A key aspect of the Smart Villages approach is that the design and development of a project, energy system, or associated intervention is led by community needs and priorities. The SVT is a first step to uncover those needs and aspirations, both for our benefit but also for the community members who participate.

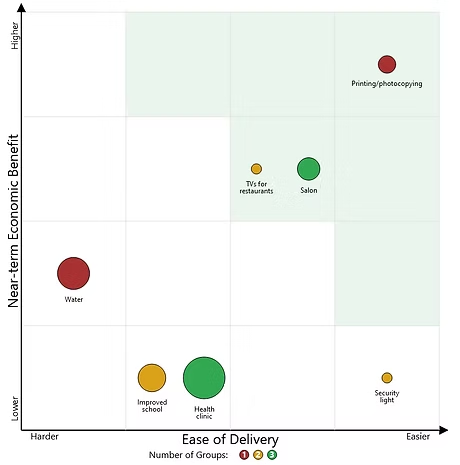

So how does it work? In the community, it takes the form of a focus group of 2-3 hours long, with approximately 10 participants. We work with multiple community segments in different focus groups to try to get a reasonable representation of views and opinions. We ask ‘what services do you need here?’, gather suggestions, and then ask people to prioritise them. Finally, we discuss the results and delve into the ‘whys’ and surrounding contextual factors. Back in the ‘office’, there’s then a process to analyse the results and present them so as to weigh up the different design decision-making criteria that influence the design of an energy project, such as – economic benefit to the community and ease of delivery. This helps guide the technical design to the system – making sure the community needs and priorities are front and centre throughout the process.

A form of the SVT was originally developed during our colleague Anna Clement’s PhD, co-created by engineers and social scientists, to assist in the design of two mini-grids in Kenya, and it’s under continual development and refinement. Further iterations of the method have been deployed in multiple SVRG projects spanning Tanzania, Uganda, Somaliland, and Lesotho. For more information on the method and analysis, click through to Anna’s website.